Jul 1st, 2024

BYE BYE, CHEVRON DEFERENCE . . . HELLO, ‘JUDGES GONE WILD’?

The Supreme Court’s June 28, 2024 decision in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo wiped away the four-decade old doctrine that reviewing courts must grant “Chevron deference” to agency regulations. The decision represents a massive shift of power away from administrative agencies and to the judicial branch of government.

Perhaps nowhere will the elimination of the Chevron doctrine be more keenly felt than in the trade courts – the United States Court of International Trade (CIT) and the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit – where virtually every Customs and trade remedy case involves a government agency party, and, in the majority of instances, the question of how an agency regulation should be interpreted or applied. But the trade courts have a unique history of defying Chevron’s command of deference to regulations—one that is worth retelling here, and which may provide an inkling of how the trade courts will act in a post-Chevron future.

The Two-Step Chevron Rule

In Chevron USA Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, 467 U.S. 837 (1984), the Supreme Court set out a two-step test for determining whether a reviewing court must defer to an agency’s interpretation of a statute, as set out in regulations adopted pursuant to the Administrative Procedure Act (APA). The issue in Chevron was the definition of the word “source” as set out in an EPA regulation defining pollution “sources”. The Court set out a two-step rule for Courts to follow:

- Chevron Step One asks whether the statute in question speaks directly to the question at hand; if so, the statute must be followed, and the inquiry ends.

- Chevron Step Two kicks in when the statute does not directly address the question and leaves a “gap” for the agency to fill by rulemaking. In those cases, the reviewing court must defer to the agency’s judgment, as expressed in the regulation, so long as it is “not unreasonable”.

The rule was a recognition that, in enacting legislation, Congress would necessarily have to speak in general terms, and could not possibly anticipate every situation which might arise in the statute’s administration. It assumed that Congress intended for the agencies administering the statute to “fill in the gaps” by enacting regulations addressing particular situations.

This command has left many a judge seething over regulations which seem suboptimal, or which reject superior interpretations, or which represent poor policy choices, but which cannot be said to be “unreasonable.” In these cases, the courts, grudgingly applying Chevron deference uphold the regulation and its application to the case at hand.

But proponents of Chevron argued that the decision drew the right balance between agency expertise and policymaking duties, and the reviewing role of the courts.

In Loper Bright, the Supreme Court overruled Chevron – or at least Chevron Step Two – holding that reviewing courts are not obligated to give any binding deference to agency regulations. This, the Court claimed, was necessary to reconcile judicial review with the APA, which says that the courts are to decide all legal questions, and to set aside agency actions which are “not in accordance with law”.

Loper Bright involved a challenge by Atlantic herring fishermen to a Commerce Department rule requiring them to pay for observers to sail with them and to monitor catch quotas. The First and DC Circuits upheld the rule on the basis of Chevron deference to agency regulations. The Supreme Court sent the cases back to the circuit courts to decide the questions before them without deference.

The Trade Courts’ History with Chevron Deference

For the first decade and a half after the Chevron decision was issued, the trade courts refused to “play ball.” The Court of International Trade, proclaiming itself a specialized court with nationwide jurisdiction, held that it had co-equal expertise with the agencies whose decisions it reviewed, and that deference to the agencies’ interpretive regulations was not due. That ended in a big way with the Supreme Court’s decision in United States v. Haggar Apparel Inc., 526 U.S. 380 (1999).

Haggar assembled trousers in Mexico using “fabricated components of United States origin,” and sought duty allowances under Harmonized Tariff Schedule subheading 9802.00.50. That statute granted benefits only if the foreign operations consisted of “assembly and operations incidental to assembly.” In addition to assembling the garment components in Mexico, Haggar performed “permapressing.” Customs denied the duty allowances based on a regulation in which it proclaimed that “permapressing” was not “incidental to assembly.”

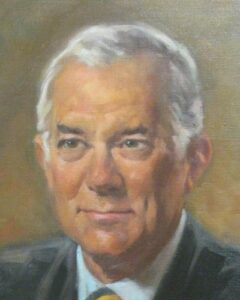

The CIT was having none of it, and in Haggar’s case, as well as a companion case, Levi Strauss & Co. v. United States, the court took evidence on the question of whether permapressing was “incidental to assembly.” The Court, per the late Judge R. Kenton Musgrave (1927-2023), noting that Customs cases were to be decided de novo on the basis of the record before the court, found that permapressing was indeed incidental to assembly and that the companies were entitled to the allowances.

On appeal, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit held that the CIT was not bound to give deference to Customs’ regulation. But an essentially unanimous Supreme Court reversed, holding that the trade courts, like any other courts, were bound to apply binding Chevron deference to agencies’ regulations. Two of the Justices—i.e., Stevens and Ginsburg—would have had the Supreme Court itself interpret the regulation, instead of remanding the issue to the lower courts.

[Notably, two years later, Customs was back at the high court seeking Chevron deference for Customs’ rulings. In United States v. Mead Corp., 533 U.S. 218 (2001), the Court declined to require such deference, instead finding that courts had the option, but not the obligation, to apply “Skidmore deference” to positions set out in agency rulings which the courts found to be reasonable, well-articulated, and consistently applied. The Loper Bright decision does not appear to affect “Skidmore/Mead” deference].

The Trade Courts Post-Haggar

The Haggar and Levi Strauss decisions eventually worked their way back to the CIT for final disposition. In the Haggar case, Judge Musgrave issued a simple order withdrawing his prior opinion and entering judgment for the government. However, in Levi Strauss Inc. v. United States, 25 C.I.T. 166 (2001), he prefaced his orders with a blistering critique of The Supreme Court, and its holdings on Chevron deference. Presaging the words of Chief Justice Roberts a quarter century hence, he thundered:

In Marbury v. Madison, Chief Justice Marshall stated that “it is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is“, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137, 177, 2 L. Ed. 60 (1803) … a position generally accepted by the bar and the judiciary for the past one hundred ninety-eight years. This proposition was significantly limited, if not partially overruled, by the Supreme Court’s decision in Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc., … which was recently reaffirmed in United States v. Haggar Apparel Co., holding that the law may be— and indeed is mandated to be—the interpretation by the agency administering the particular law or regulation.

Id. at 166-67 (internal citations omitted) (emphasis added).

“Thus an agency employee, who may have little or no background in the law, is now both the enforcer and interpreter of the law,” the Judge noted. Id. at 167. “This result compromises the long established concept of judicial review.” Id. A quarter century later, a Supreme Court majority would agree.

Judge Musgrave also criticized Federal Court decisions saying that the Commerce Department is entitled to tremendous deference in the administration of the trade remedy statutes and that the International Trade Administration (ITA) is “the master of the dumping law.”

Judge Musgrave also criticized Federal Court decisions saying that the Commerce Department is entitled to tremendous deference in the administration of the trade remedy statutes and that the International Trade Administration (ITA) is “the master of the dumping law.”

Following the Supreme Court’s Loper Bright decision, Judge Musgrave’s Levi Strauss decision from nearly a quarter century earlier is an interesting read.

The Trade Courts Post-Loper Bright

Buckle your seatbelts: it could be a bumpy ride. While Loper Bright represents a tremendous transfer of power to the judiciary, nowhere is that truer than in Customs and Trade cases. Judges who have seethed about particular regulations, but grudgingly applied them, citing Chevron, are free to chart a different course. Advocates for parties opposing the government in these cases are largely liberated from the yoke of Chevron deference. While some have said that the Chevron doctrine promoted more uniform outcomes, we might expect to see less uniformity in judicial decisions going forward. The current CIT bench includes deference skeptics and judges who have held senior positions in administrative agencies.

And in Washington, “Master of the Dumping Law” t-shirts may become collectibles.